By Venetia Rainey in Beirut

DAY 1

This is Ali.

Ali is from Bourj al-Barajneh, the largest of the four official Palestinian camps in Beirut's suburbs, and one of the most overcrowded. He's 25 and has lived all his life in a small, four-room apartment in the camp with his mum, dad and two brothers. He's mostly made his peace with that, although he admits he has tried to escape to Europe. He knows plenty of people who have done it, but his attempt failed at the first hurdle: he didn't manage to get a visa for Turkey. Bourj al-Barajneh is one of those places you want to escape from, he explains in his soft, gentle voice. Thick, deadly tangles of electricity cables form a sort of canopy over the narrow alleyways and, thanks to the achingly old sewage system, winter means flooding and bad smells whenever it rains.

Bourj al-Barajneh is overcrowded and residents complain about the dangerous electricity cables that hang low (Magne Hagesæter/Flickr)

DAY 2

(Venetia Rainey/IRIN)

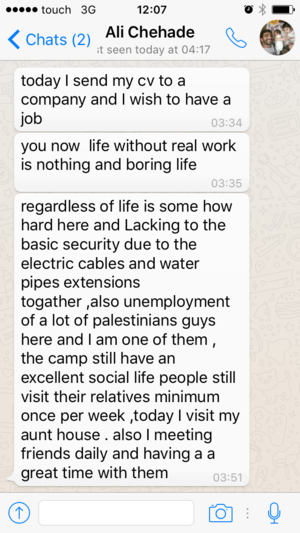

Ali is a real family guy. He enjoys having tea with relatives and loves to spend time playing with his niece, who is two and a half years old. When he's not doing that, he kicks a ball around, smokes shisha with his friends, plays computer games at a local internet cafe, or works on his pet project: an Android app that allows you to meet people online. He taught himself how to code through YouTube tutorials, but in order to do that, he first had to teach himself English, which he also did online. The UNRWA-run schools in the camp aren't much good, he says with a shrug, so you have to do it yourself. He's heard whispers that in the next few years there might not even be an UNRWA, a common rumour in the country following the introduction of the health aid cuts in Lebanon at the beginning of this year.

Such rumours are not true, but UNRWA is certainly facing the greatest funding crisis in its 65-year history, and was on the brink of postponing classes in almost 700 schools for Palestinians throughout the region last September due to a lack of money. The crisis was averted at the last minute, but with UNRWA facing a 2016 budget shortfall of $81 million and an ever-growing Palestinian population utterly dependent on the agency, the spectre of further reduced services looms large. For young people like Ali in Lebanon - where Palestinian refugees are socially, economically, politically and legally excluded - UNRWA is the only ray of hope, and education is the best chance at a better life.

ALI'S PHOTOS OF BOURJ AL-BARAJNEH

DAY 4

Ali hasn't found a fulltime job, and finds it hard to work from home with the frequent power cuts (Venetia Rainey/IRIN)

Out of the 280,000 Palestinian refugees currently estimated to be living in Lebanon, nearly all are classified as foreigners under Lebanese law, despite the fact that more than 90% were born in the country and have spent their whole lives there. This ruling has huge ramifications for the population, not least of which is the severe labour restrictions it places on them. The combination of limited job opportunities, discriminatory attitudes and legal obstacles means that many Palestinians must accept whatever work they can find, no matter the legal or financial terms, according to a 2012 International Labour Organisation report.

DAY 5

DAY 7

When he reflects on camp life in Bourj al-Barajneh, Ali is pragmatic. It's not all bad; he has his family and friends, and they provide much of his happiness. But there are a lot of negatives, and he knows them all inside out – he experiences them every day. Nothing is a sure thing for his generation. On top of the bigger, ordinary demands of growing up – finding a job, keeping in good health, maintaining relationships with friends and family – Ali faces hundreds of tiny, more specific challenges. Overcrowding – in part due to the arrival of Syrian refugees in the past few years – dangerous living conditions, punishing labour laws and a community-wide dependence on an underfunded aid agency all combine to make life like walking a never-ending tightrope.